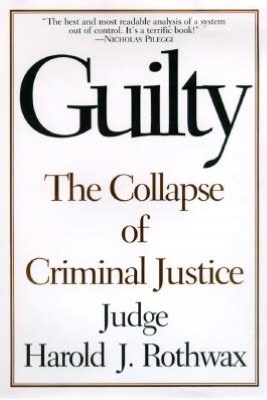

There is a genre of writing about criminal law and the criminal justice system that presents the story of modern criminal justice as one of decline. There was a golden age at some point in the past - though precisely when this was depends on the thesis being advanced in the book - and the subsequent history is presented as a fall from grace. Ideals of clarity, simplicity and justice are departed from as the system becomes increasingly complex and bureaucractised. And the solution is always to go back to the future, a return to the model of the past as a way of moving forward.

An excellent example of this type of narrative is William Stuntz's The Collapse of American Criminal Justice (2011), a work which has been highly praised by reviewers. The diagnosis of the ills of the system is a largely familiar one. It is highly discriminatory against poor and black individuals and communities; punishments are increasingly harsh; and the rule of law has been increasingly undermined by official discretion in law enforcement - from the police deciding who to stop and search to the use of plea bargaining to replace jury trials, to legislative practices which have allowed the creation of broad offence definitions which ease the practice of enforcement. These three factors interact as discretion reinforces discrimination. These are then read through a historical narrative which tells the story of the departure of criminal justice from Golden (or rather Gilded) Age ideals. Stuntz is too smart to completely romanticise the past, but he still anchors the account in an appeal to simpler times.

These simpler times are seen in what has become known as the 'Gilded Age', roughly between 1880 and 1930. And this is read for two main factors. First, he claims that the system was more democractic, in the sense that there was greater local accountability, and second he argues that this system actually fostered greater commitment to the ideal of equal protection before the law. His account of this is complex and nuanced, but basically boils down to the idea that law enforcement officers lived in the communities where they enforced the law and juries comprised of local citizens had greater freedom to interpret how legal norms could be applied then this represented a check on state power, which was gradually undermined as the system was bureaucratised and made less accountable. More controversially, he argues that the due process reforms of the Warren Court in the 1960s were wrong because they undermined the pre-existing commitment to equal protection before the law.

There is a nostalgia for the past in this kind of thesis, that inevitably underplays certain features of the historical systems in favour of those which are seen to support the argument. However, rather than challenge the history with an alternative interpretation (which I am not sure that I am qualified to do), I am more interested in the structure of the argument. First of all, the nostalgia here, the appeal to simpler times, is deeply conservative. In spite of Stuntz's admission that he is primarily concerned with contemporary problems, this kind of move seems to me to express a desire not to engage with the present, to avoid the complexity of now by turning back the clock. Indeed the argument in the book works best when it drops the historical comparison and simply looks with a critical eye at developments in sentencing or policing. Nostalgia also inevitably underplays the complexity of the past, as we can appeal to an image that reinforces our existing prejudices. There is not a genuine historical interest here, because the argument is already known. And this points to the third move - redemption. We can be saved if we believe, but then the argument is itself predestined.

For some reason this genre seems particularly prevalent in the US - try googling collapse of american criminal justice and see how many examples come up. This may just be because dramatic titles sell books (collapse, decline, fall, death), but it probably also connected to something deeper. There is a lingering distrust of the state, evidenced in the faith in the original words or motives of the framers of the constitution, or the persistent desire to see their political system through the lens of de Tocqueville (a French tourist who showered it with praise in the 1820s). This might even be seen as a faltering commitment to modernity. Whatever it is, it is important in engaging with this to think not just of content, but also the form in which it is expressed.

This is a blog about the history, theory and practice of the criminal law. I shall write about books, cases, trials, novels that catch my interest, and even occasionally about current events. My aim is not comment on current caselaw or issues in criminal justice, but to rather to develop a more oblique critique of the law.

Oblique intent

Why the name? Well criminal law afficionados will recognise the phrase 'oblique intent' as referring to a problem of mens rea:can a person who intends to do x (such as setting fire to a building to scare the occupants) also be said to have an intention to kill if one of the occupants dies? This is a problem that has consumed an inordinate amount of time in the appeal courts and in the legal journals, and can be taken to represent a certain kind of approach to legal theory. My approach is intended to be more oblique to this mainstream approach, and thus to raise different kinds of questions and issues. Hence the name.

Friday 26 October 2012

Thursday 11 October 2012

On the (de-)criminalization of HIV transmission again

It occurs to me that the conclusion to the last post was rather rushed - a bit too oblique, if you like - and that I could have spelled out my concerns in more detail. I am also prompted to do this because I have been shown some further research on prosecutions for HIV transmission in Canada which underlines some of the points I was wanting to make in the post.

Criminalization or decriminalization in this area is always also about the distribution of responsibilities. Does the state take responsibilty for managing public health in this area, or does it pass the responsibility on to others - or does it share the responsibilities in an appropriate way? The use of the law in this area requires us to reflect on what it is that we seek to achieve through the use of the criminal law - the public health dimension, if you like. It is not only a matter of a harm being done to someone (the transmission of HIV), but also of whether the use of the criminal law is the best means of harm reduction. And in a situation where (at least) two people are involved, it is not always going to be easy to point the finger of blame at one of them. Who should take responsibilty for disclosure? Who is expected to take precautions (and who will be prosecuted for the failure to take precautions)? This also relates to our perception of who the victim is in a given situation, and who can be viewed as a perpetrator or which group of people represent a threat.

Criminalization or decriminalization in this area is always also about the distribution of responsibilities. Does the state take responsibilty for managing public health in this area, or does it pass the responsibility on to others - or does it share the responsibilities in an appropriate way? The use of the law in this area requires us to reflect on what it is that we seek to achieve through the use of the criminal law - the public health dimension, if you like. It is not only a matter of a harm being done to someone (the transmission of HIV), but also of whether the use of the criminal law is the best means of harm reduction. And in a situation where (at least) two people are involved, it is not always going to be easy to point the finger of blame at one of them. Who should take responsibilty for disclosure? Who is expected to take precautions (and who will be prosecuted for the failure to take precautions)? This also relates to our perception of who the victim is in a given situation, and who can be viewed as a perpetrator or which group of people represent a threat.

Answers to these kind of questions are given some content by research which has been carried out on who is prosecuted for the crime of HIV transmission in Canada and for what kind of sexual encounters. There is a lot of fascinating material in the report, but I want to pull out two key findings. These are first that in a high percentage of the prosecutions (40%) no actual HIV transmission had taken place - that is to say that the person was being prosecuted for an aggravated sexual offence where what was at issue was the risk of serous bodily harm. Second, the majority of those prosecuted were heterosexual men (around 70%) - which is to say those who were prosecuted on the basis of a heterosexual encounter - and in the period since 2004 the majority of these were black. In seeking to explain this last finding, the authors of the report make two observations. The first is that this might reflect differences in understandings of and respones to HIV risk between the gay and heterosexual communities. And second, they suggest that heterosexual women, and especially white heterosexual women, who are the complainants in many of these cases better fit police and prosecution conceptions of victims - and so the cases are more likely to be taken up.

Answers to these kind of questions are given some content by research which has been carried out on who is prosecuted for the crime of HIV transmission in Canada and for what kind of sexual encounters. There is a lot of fascinating material in the report, but I want to pull out two key findings. These are first that in a high percentage of the prosecutions (40%) no actual HIV transmission had taken place - that is to say that the person was being prosecuted for an aggravated sexual offence where what was at issue was the risk of serous bodily harm. Second, the majority of those prosecuted were heterosexual men (around 70%) - which is to say those who were prosecuted on the basis of a heterosexual encounter - and in the period since 2004 the majority of these were black. In seeking to explain this last finding, the authors of the report make two observations. The first is that this might reflect differences in understandings of and respones to HIV risk between the gay and heterosexual communities. And second, they suggest that heterosexual women, and especially white heterosexual women, who are the complainants in many of these cases better fit police and prosecution conceptions of victims - and so the cases are more likely to be taken up.

The way forward must surely be shared responsibility for the disclosure and for the consequences of non-disclosure. Where no transmission takes place it is hard to see what is achieved through criminal prosecution - other than the reinforcement of prejudice. And even where there is transmission it is hard to see that the criminal law has a role to play, except in cases where this is deliberate and some overt deception or fraud has been used.

Criminalization or decriminalization in this area is always also about the distribution of responsibilities. Does the state take responsibilty for managing public health in this area, or does it pass the responsibility on to others - or does it share the responsibilities in an appropriate way? The use of the law in this area requires us to reflect on what it is that we seek to achieve through the use of the criminal law - the public health dimension, if you like. It is not only a matter of a harm being done to someone (the transmission of HIV), but also of whether the use of the criminal law is the best means of harm reduction. And in a situation where (at least) two people are involved, it is not always going to be easy to point the finger of blame at one of them. Who should take responsibilty for disclosure? Who is expected to take precautions (and who will be prosecuted for the failure to take precautions)? This also relates to our perception of who the victim is in a given situation, and who can be viewed as a perpetrator or which group of people represent a threat.

Criminalization or decriminalization in this area is always also about the distribution of responsibilities. Does the state take responsibilty for managing public health in this area, or does it pass the responsibility on to others - or does it share the responsibilities in an appropriate way? The use of the law in this area requires us to reflect on what it is that we seek to achieve through the use of the criminal law - the public health dimension, if you like. It is not only a matter of a harm being done to someone (the transmission of HIV), but also of whether the use of the criminal law is the best means of harm reduction. And in a situation where (at least) two people are involved, it is not always going to be easy to point the finger of blame at one of them. Who should take responsibilty for disclosure? Who is expected to take precautions (and who will be prosecuted for the failure to take precautions)? This also relates to our perception of who the victim is in a given situation, and who can be viewed as a perpetrator or which group of people represent a threat. Answers to these kind of questions are given some content by research which has been carried out on who is prosecuted for the crime of HIV transmission in Canada and for what kind of sexual encounters. There is a lot of fascinating material in the report, but I want to pull out two key findings. These are first that in a high percentage of the prosecutions (40%) no actual HIV transmission had taken place - that is to say that the person was being prosecuted for an aggravated sexual offence where what was at issue was the risk of serous bodily harm. Second, the majority of those prosecuted were heterosexual men (around 70%) - which is to say those who were prosecuted on the basis of a heterosexual encounter - and in the period since 2004 the majority of these were black. In seeking to explain this last finding, the authors of the report make two observations. The first is that this might reflect differences in understandings of and respones to HIV risk between the gay and heterosexual communities. And second, they suggest that heterosexual women, and especially white heterosexual women, who are the complainants in many of these cases better fit police and prosecution conceptions of victims - and so the cases are more likely to be taken up.

Answers to these kind of questions are given some content by research which has been carried out on who is prosecuted for the crime of HIV transmission in Canada and for what kind of sexual encounters. There is a lot of fascinating material in the report, but I want to pull out two key findings. These are first that in a high percentage of the prosecutions (40%) no actual HIV transmission had taken place - that is to say that the person was being prosecuted for an aggravated sexual offence where what was at issue was the risk of serous bodily harm. Second, the majority of those prosecuted were heterosexual men (around 70%) - which is to say those who were prosecuted on the basis of a heterosexual encounter - and in the period since 2004 the majority of these were black. In seeking to explain this last finding, the authors of the report make two observations. The first is that this might reflect differences in understandings of and respones to HIV risk between the gay and heterosexual communities. And second, they suggest that heterosexual women, and especially white heterosexual women, who are the complainants in many of these cases better fit police and prosecution conceptions of victims - and so the cases are more likely to be taken up.

So, if we go back to the discussion of the case, can we draw any further conclusion. It is arguable that the Court was trying to address the first point - decriminalising non-disclosure where there is no significant risk of transmission. But the real risk here is that this aim will be undermined by the lack of attention to the context in which sexual encounters take place and the failure to specify clearly where responsibilities lie. In fact it is arguable that the finding of the case - restoring the convictions against a black Sudanese immigrant where the female complainants testified about their fears - in fact reinforces the prejudices in this area.

The way forward must surely be shared responsibility for the disclosure and for the consequences of non-disclosure. Where no transmission takes place it is hard to see what is achieved through criminal prosecution - other than the reinforcement of prejudice. And even where there is transmission it is hard to see that the criminal law has a role to play, except in cases where this is deliberate and some overt deception or fraud has been used.

Monday 8 October 2012

On the (de-)criminalization of HIV transmission

The recent judgment of the Supreme Court of Canada in the case of R v Mabior raises some interesting issues about the criminalization of HIV transmission. The case involved a man who was charged with nine charges of aggravated sexual assault under the Canadian Criminal Code for failure to disclose his HIV status to his sexual partners. In this case none of these sexual partners contracted HIV. There was also evidence either that a condom had been used, or that as the man was using retroviral drugs, his viral load was low and there was accordingly a low risk of transmission of the virus. The case accordingly concerned the questions of the degree of risk required to constitute the crime, and of the kind of risk might or might not be consented to and the sort of information that was necessary to make consent real.

He was initially convicted of aggravated assault, but on appeal the convictions were negated on the grounds that the low risk of transmission could mean that the offence had not been committed. The Crown appealed against this and the Supreme Court restored the convictions in four of the cases -where in spite of the low risk of transmission the complainants had testified that had they known of Mabior's HIV status they would not have had sex with him.

The case had been regarded as an important opportunity to reframe Canadian law on this issue. There was evidence to suggest that the level of prosecutions for this offence in Canada was high, and an unease about treating this as a serious life endangering offence in an era where improved drug treatment limited the impact of transmission. It is harder to argue that HIV is life endangering, at least in Canada and other western countries where the availability of retroviral drugs means that the illness can be managed. There was thus an argument that the offence had been drawn on overly broad terms, given its seriousness, and for limiting the role of the criminal law in this area.

The case had been regarded as an important opportunity to reframe Canadian law on this issue. There was evidence to suggest that the level of prosecutions for this offence in Canada was high, and an unease about treating this as a serious life endangering offence in an era where improved drug treatment limited the impact of transmission. It is harder to argue that HIV is life endangering, at least in Canada and other western countries where the availability of retroviral drugs means that the illness can be managed. There was thus an argument that the offence had been drawn on overly broad terms, given its seriousness, and for limiting the role of the criminal law in this area.

The basic Canadian law in this area was established in the case of Cuerrier in 1998. In this case the Supreme Court ruled that failure to disclose that one has HIV could constitute fraud vitiating consent to sexual relations under s. 265(3)(c) of the Canadian Criminal Code and amount to aggravated sexual assault (s.273). (This, I should add, is already a stretch. Section 265 talks about applying force to another, and aggravated sexual assault is defined in terms of wounding, maiming, disfiguring or endangering the life of another - none of which are terms that easily fit in this area). So, in order to establish a conviction, the Crown must show a dishonest act which affected the ability of the complainant to consent (lying about the one's HIV status) and that this endangered life.

The decision in Mabior does not change the basic law in this area - an intentional failure to disclose HIV status can still amount to aggravated sexual assault - but it does try to clarify the circumstances under which discloure of HIV status might be necessary. For the sake of simplicity, the new test can be understood as comprising an objective and a subjective element. Objectively the Court states that in order for it to be necessary to disclose your HIV status there must be a 'significant risk' of transmission. Accordingly, where the risk of transmission is low it may not be necessary to inform prospective sexual partners of your HIV status (though the judgment is somewhat vague here as to whether it is also necessary to use a condom). In the subjective part of the test (which is not so clearly expressed) the Court seems to indicate that consent should be informed - that sexual partners should have the information necessary to enable them to make and informed decision as to consent.

And here we see the problem. While the Court is to be applauded for attempting to restrict the scope of the offence in the objective part, because it is not possible (as they acknowledge) to define the exact level of risk at which disclosure is not required, a lot will then depend on the subjective part of the test. But it is not clear this will limit the offence. In the appeal the convictions were restored because the complainants testified that they would not have slept with him even given the negligible risk of transmission if they had known of his HIV status. The scope of the offence thus depends on the fears of potential victims, apparently even if these are unreasonable - and the laudable aspiration to protect informed consent can quickly collapse into uninformed prejudice. A proper test in this area must be based on something more objective.

He was initially convicted of aggravated assault, but on appeal the convictions were negated on the grounds that the low risk of transmission could mean that the offence had not been committed. The Crown appealed against this and the Supreme Court restored the convictions in four of the cases -where in spite of the low risk of transmission the complainants had testified that had they known of Mabior's HIV status they would not have had sex with him.

The case had been regarded as an important opportunity to reframe Canadian law on this issue. There was evidence to suggest that the level of prosecutions for this offence in Canada was high, and an unease about treating this as a serious life endangering offence in an era where improved drug treatment limited the impact of transmission. It is harder to argue that HIV is life endangering, at least in Canada and other western countries where the availability of retroviral drugs means that the illness can be managed. There was thus an argument that the offence had been drawn on overly broad terms, given its seriousness, and for limiting the role of the criminal law in this area.

The case had been regarded as an important opportunity to reframe Canadian law on this issue. There was evidence to suggest that the level of prosecutions for this offence in Canada was high, and an unease about treating this as a serious life endangering offence in an era where improved drug treatment limited the impact of transmission. It is harder to argue that HIV is life endangering, at least in Canada and other western countries where the availability of retroviral drugs means that the illness can be managed. There was thus an argument that the offence had been drawn on overly broad terms, given its seriousness, and for limiting the role of the criminal law in this area. The basic Canadian law in this area was established in the case of Cuerrier in 1998. In this case the Supreme Court ruled that failure to disclose that one has HIV could constitute fraud vitiating consent to sexual relations under s. 265(3)(c) of the Canadian Criminal Code and amount to aggravated sexual assault (s.273). (This, I should add, is already a stretch. Section 265 talks about applying force to another, and aggravated sexual assault is defined in terms of wounding, maiming, disfiguring or endangering the life of another - none of which are terms that easily fit in this area). So, in order to establish a conviction, the Crown must show a dishonest act which affected the ability of the complainant to consent (lying about the one's HIV status) and that this endangered life.

The decision in Mabior does not change the basic law in this area - an intentional failure to disclose HIV status can still amount to aggravated sexual assault - but it does try to clarify the circumstances under which discloure of HIV status might be necessary. For the sake of simplicity, the new test can be understood as comprising an objective and a subjective element. Objectively the Court states that in order for it to be necessary to disclose your HIV status there must be a 'significant risk' of transmission. Accordingly, where the risk of transmission is low it may not be necessary to inform prospective sexual partners of your HIV status (though the judgment is somewhat vague here as to whether it is also necessary to use a condom). In the subjective part of the test (which is not so clearly expressed) the Court seems to indicate that consent should be informed - that sexual partners should have the information necessary to enable them to make and informed decision as to consent.

|

| But is always necessary to use one? |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)